Ingression within mathematics: Pattern ingression as questions asked by indexing categories

There’s something in math itself that looks like pattern ingression, where a simple pattern in one category can be used to organize the construction of a more elaborate structure in another category. This something is categorical limits (and colimits).

I’ve been writing a lot about the Cartesian product, which is a convenient example for understanding limits as well. The Cartesian product is defined by a universal property. Limits are a systematic way of thinking about universal properties that let us search for the same property in different domains without having to change anything about what we’re looking for.

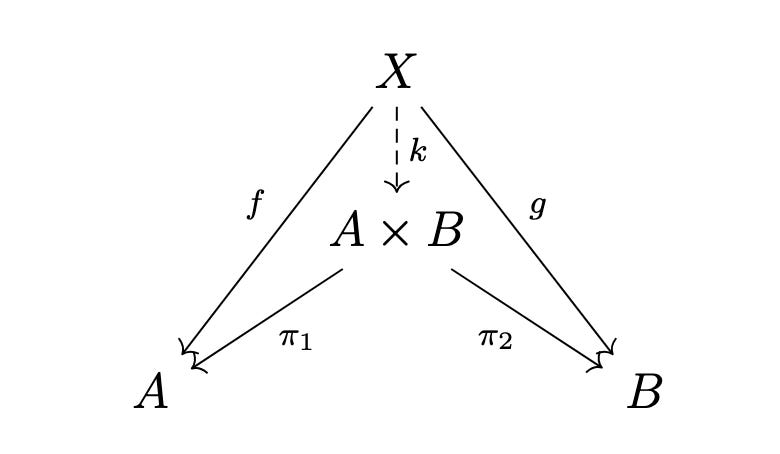

As a reminder, the Cartesian product is a structure that looks like this:

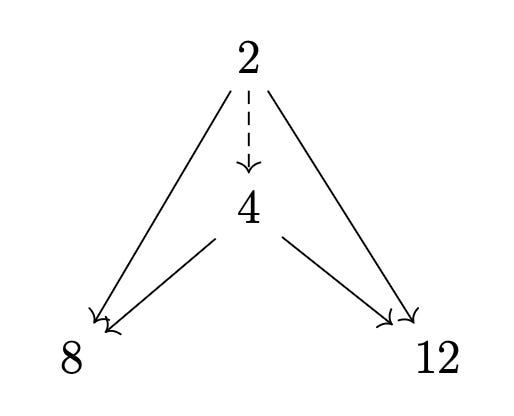

where A, B, AxB, and X are all sets, and the arrows are all functions. The exact same pattern is seen in many different contexts. For example, consider the divisibility of the nonzero natural numbers. We can draw an arrow from one number to another to denote the fact that the first number divides the second number. E.g., 2 → 4 would mean that 2 divides 4, in which case we say that 2 is a divisor of 4. We wouldn’t have an arrow like 2 → 5 because 5 divided by 2 doesn’t give a natural number. The arrow only exists if it’s a nice, clean division with no remainder.

Every pair of numbers has a set of common divisors, numbers that divide both elements of the pair. For example, 2 → 8 and 2 → 12, so 2 is a common divisor of 8 and 12. But it’s not the only one. Another common divisor is 4 since 5 → 8 and 5 → 12. In fact, 4 is the greatest common divisor, or gcd, of 8 and 12: all of the other common divisors of 8 and 12, namely 1 and 2, are less than 4.

Not coincidentally, 1 and 2 are also the divisors of 4. If we consider the work that 4 does to divide 8 and 12, there’s an intuitive sense in which 4 summarizes the divisibility relationships that 1 and 2 have with 8: If you know 4 is the divisor of two numbers, then you know 1 and 2 divide them as well. The greatest common divisor, 4, is in this sense the best way to divide both 8 and 12: saying that 4 divides 8 and 12 communicates more divisibility information than saying that any other common divisor divides 8 and 12.

If we draw the relationship between 2 and 4 diagramatically in terms of how they divide 8 and 12, we get this.

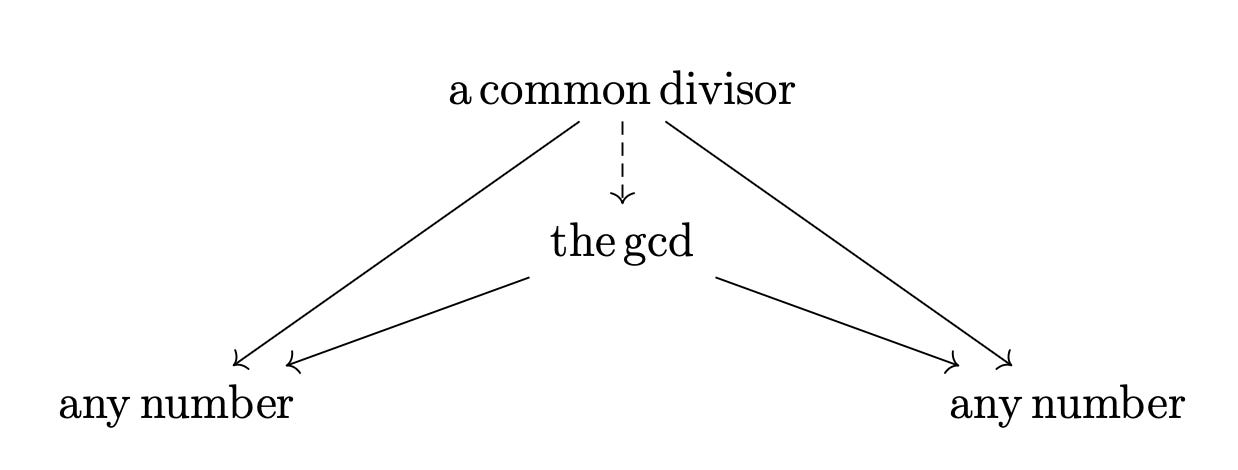

The arrows denote divisibility. The arrow from 2 to 4 is dashed to denote that it is unique (there’s only one way to divide 4 by 2), although in this category all the arrows are unique so it’s a bit redundant. More generally, we have this diagram:

This diagram looks exactly like the diagram for the Cartesian product. This is because they are the same pattern, the categorical product in different contexts. The Cartesian product is the product in the category of sets, while the greatest common divisor is the product in the category where objects are natural numbers greater than 0 and the relations between the objects are divisibility. But the underlying pattern of the categorical product is the same.

Limits are the way we talk about how the same underlying patterns in different categories. These underlying patterns, the universal properties, are optimal solutions to optimization problems. But for any given category, we don’t know what optimal solutions might exist, and we don’t have a principled way of searching for them within the category. Limits are a context-independent way of defining the optimization problem so that we can then search for optimal solutions anywhere.

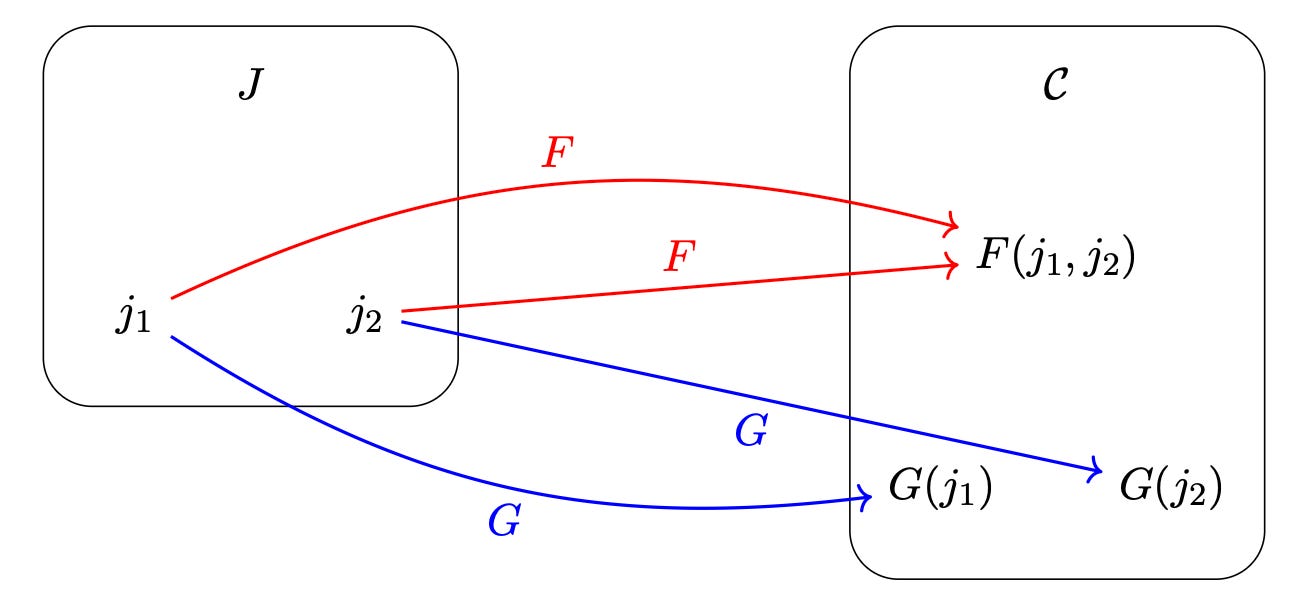

The way limits work is to take an indexing category that defines the optimization problem, and then a map from the indexing category to any other category lets us define the optimal solution in a category-independent manner.

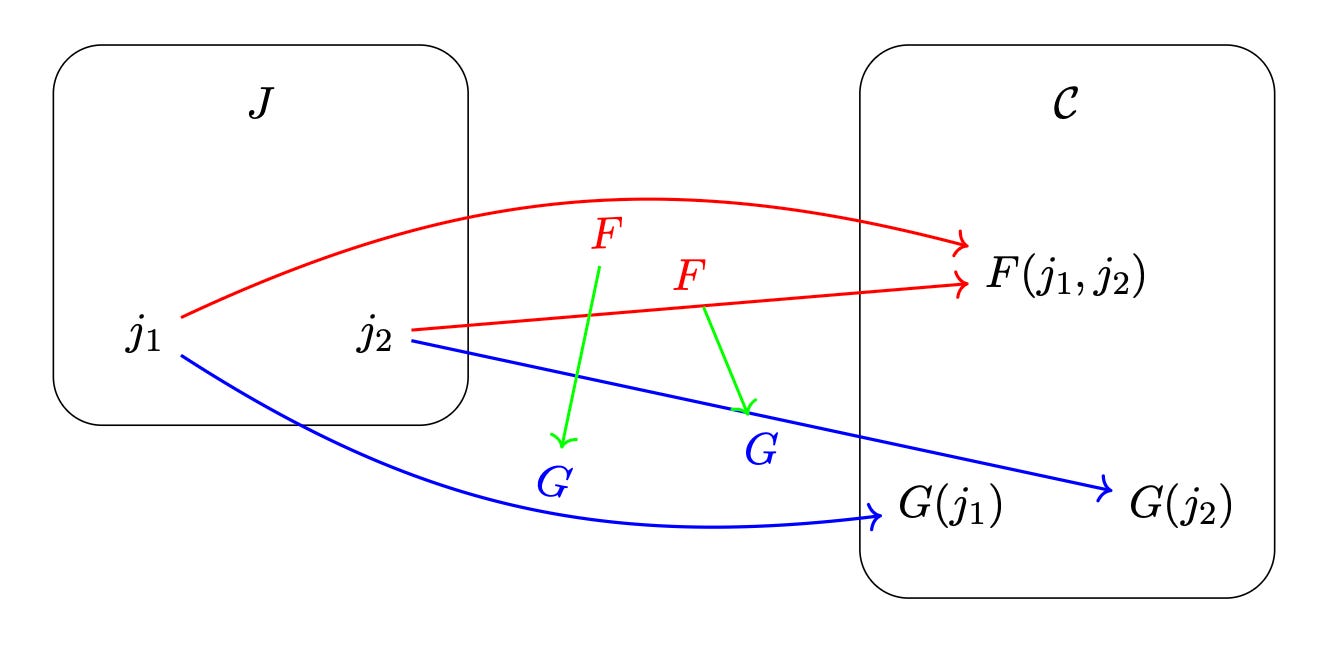

So what is the optimization problem? Every universal property is defined in terms of doing an optimal job of relating to some objects in the system as denoted by arrows, whether that’s the Cartesian product AxB relating to A and to B via the two arrows going out of it, or the greatest common divisor 4 relating to 8 and to 12 via the two arrows going out it. In this case, the underlying optimization problem being asked is, “Do you have an object that relates to two other objects in an optimal way?” So to pose the optimization problem, the indexing category for the underlying pattern we’ve been looking at is just a category with two objects. Then we just consider how that category J relates to other categories C via maps like F and G.

To produce the kind of arrows we want in C, we actually just look for a way of relating F to G.

I’ll skip the details, but if we are able to proceed in a sensible way, the result would be relationships in C like so:

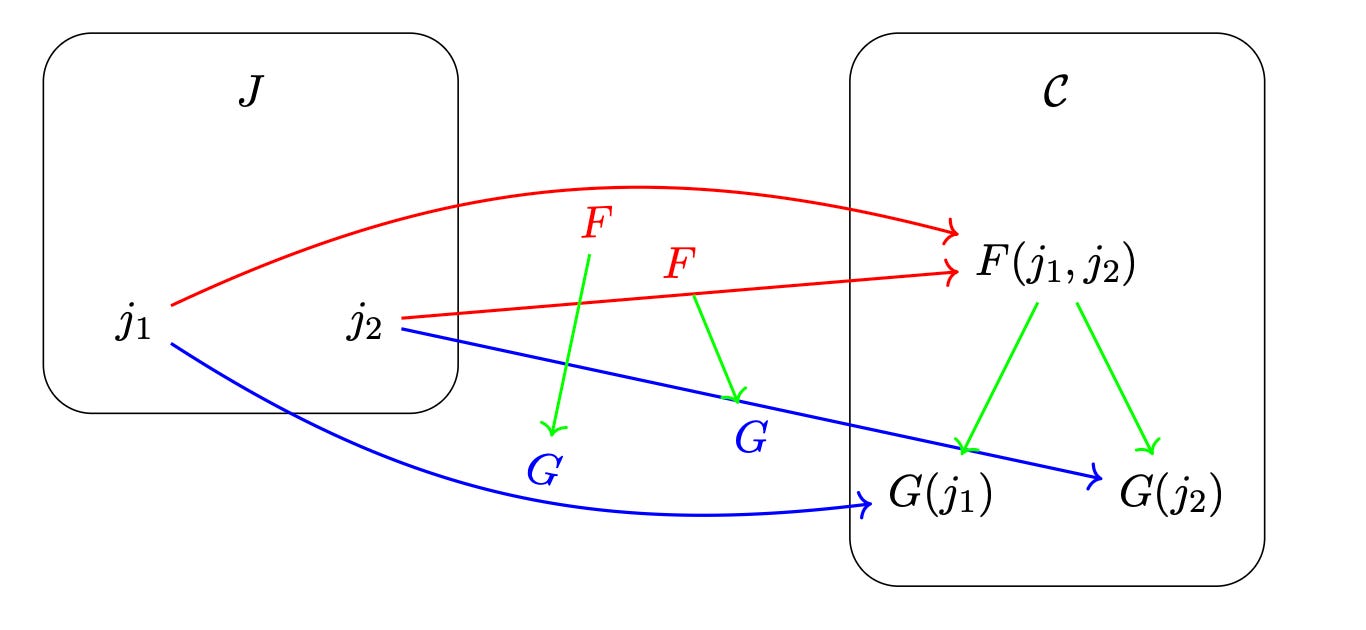

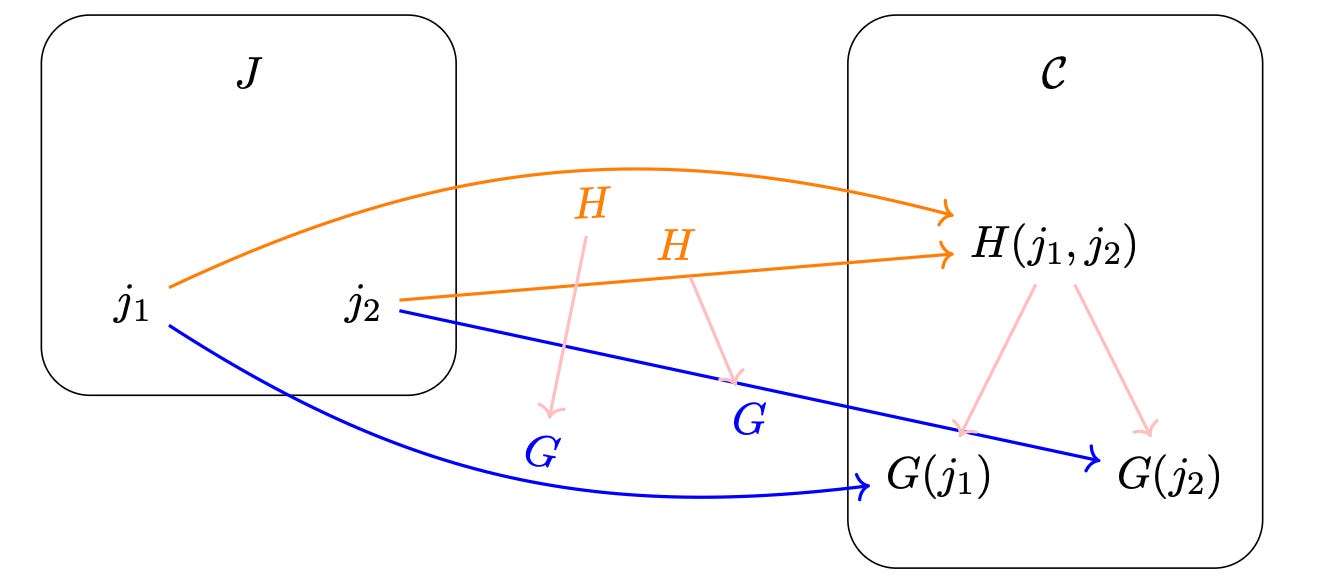

So the object being mapped to via F looks like a candidate for the universal property of the product, the optimal solution to the optimization problem we’re inquiring about. We just need to compare it to every other candidate in C. To do this, we find other candidates via other maps like so:

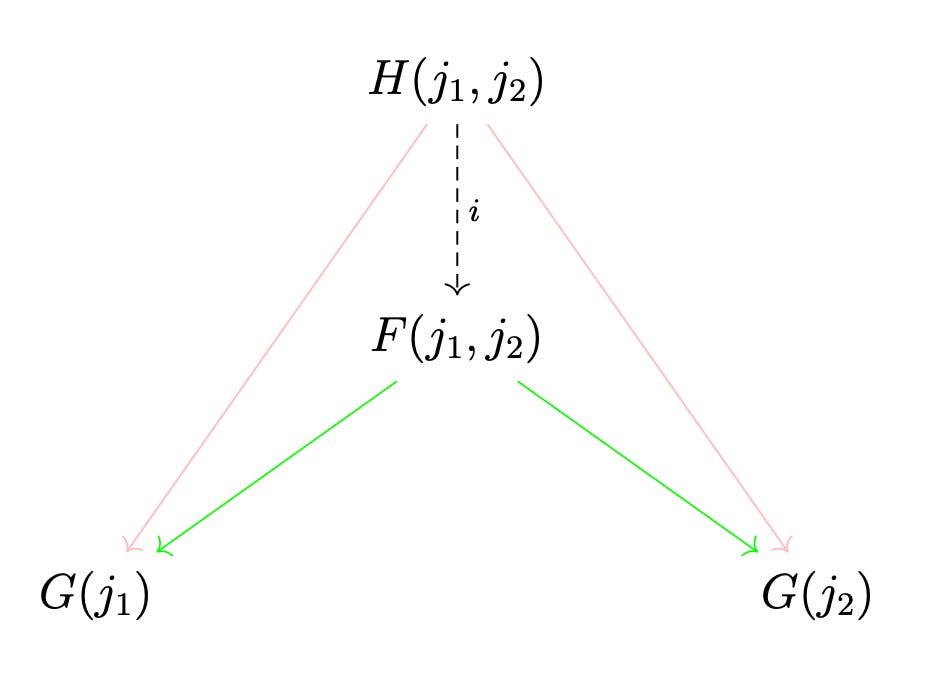

Then it’s just a matter of comparing our candidates in C. If there’s a unique morphism i from the latter candidate to the former such that this diagram commutes, then the former candidate is the optimal one. This means that if C were the category of sets, the optimal candidate would be the Cartesian product of the two objects it has arrows pointing to, and if C were the category of divisibility of natural numbers, then the optimal candidate would be the greatest common divisor of the two objects it has arrows pointing to.

So by using those maps like F, G, and H, we can pull in the pattern from J into an arbitrary category C and see if there’s an optimal solution in C. The ingressing patterns from J do all the work of defining the optimization problem and constructing all of the candidates for the optimal solution. The only work that C does is comparing all the candidates to figure out which, if any, are optimal.

The indexing category basically has a way of poking its head into any other category and saying, “Here’s a problem, here’s the format a solution should take. Do you have an optimal solution?” And the category being observed can then say yes or no, and if yes, then what the optimal solution is within that category. Additionally, the problem-solution pattern doesn’t fully exist within J or within C but is multicausally assembled in the relationships between them.

There are many relations that could be considered in C, and J basically guides C to look at what’s important. So ingression in this context is a realized capacity to construct an efficient form thanks to being prompted by another category that has the base pattern that defines the optimization problem for which a form can be efficient or inefficient. It’s like the system that is C is a pile of possible solutions, or solution-ingredients, waiting around for a problem to help them organize into a particular solution.