The Cartesian product as a virtual governor

A virtual governor is a system-level preference embodied in the relationships between the members of the system. The old, canonical example of a virtual governor is Adam Smith’s invisible hand: the coordinating forces of the economy guide people to behave according to a single economy-wide plan. The person whose plan that is is the same person whose invisible hand guides our behavior, aka, the virtual governor.

The term “virtual governor” comes from Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, who observed that a system of electrical generators behaved as if their was a system-level governor that managed the system more accurately than the governor of any individual generator. Since this system-level governor doesn’t have a concrete existence but exists among the relationships in the systems, he called it a virtual governor.

Since virtual governors exist among systems of inanimate objects such as electrical governors, they might be much more common than one might ordinarily expect. I think that mathematical structures such as the Cartesian product are also examples of virtual governors.

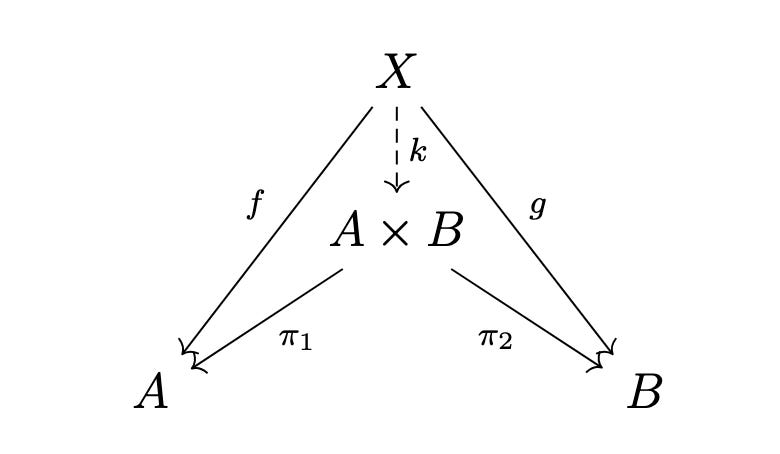

To see this, observe that the Cartesian product A x B is a kind of template for how to organize sets: If you have sets A and B, then the set labeled A x B with functions π1 and π2 to A and B, respectively is the Cartesian product of A and B when for all other sets X with functions f and g to A and B respectively, there is a unique function k from X to A x B such that the following diagram commutes.

What really matters about this diagram is the relational requirements: projection maps to the two targets A and B from the set in the middle, A x B, functions with corresponding targets from X, and most critically of all, a function k from X to A x B that identifies A x B and its two projection functions as an optimal choice for fulfilling the required role in the system.

If you change out the objects in the diagram but keep the relational requirements, the system reorganizes according to a system-level preference. For example, if you change A and B for sets of different cardinalities, then A x B and its projection functions have to get swapped out for some other triplet that fulfills what the system desires. If you even add additional sets C, D, etc., to be projected to so that we’re considering a Cartesian product of three or four sets, etc., the system-level requirements make the choice as to what A x B needs to be replaced with and how to determine which additional projection functions are required by the system. There’s an anatomical homeostasis implied in the diagram that maintains a certain structure as specific parts of the system get taken out, swapped around, or added in.

There is a real system-level preference embodied in the diagram. Any set, not just A x B, can be considered as a candidate for the Cartesian product. Some of those sets, specifically any set with the same cardinality as the set A x B, are in fact uniquely isomorphic to A x B in terms of the job it does at being the Cartesian product, meaning that these other sets with the same cardinality do just as good a job of occupying the role that A x B plays in the above diagram. All sets can be ordered with respect to each by how well they perform the role of A x B in terms of how many of these unique isomorphisms them have with A x B (i.e., one or none), resulting in a preference order over candidate Cartesian products. So there really is a system-level preference embodied in the relationships among the members of the system! This shows that the Cartesian product itself as this system, this template for how to solve a kind of optimization problem, is a virtual governor. The functions that do the coordinating act like a cognitive glue, getting the sets to talk to each other in such a way that they all figure out how to relate to each other.

If you think of the diagram as the mathematical system’s anatomy, then the functional relationships together create something akin to anatomical homeostasis over the system. As we observed, if you mess around with the objects in the system but maintain the relational requirements, then it becomes self-evident as to how all the members of the system should adjust to any changes. No individual set cares about the anatomy of the whole system, but the relational structure guides it as if by an invisible hand to behave as if it cares. The result is that the system behaves as if it’s allocating scarce resources, removing sets that don’t do a good job and bringing in sets that do.

Since the Cartesian product has preferences and puts a kind of pressure on the system to achieve those preferences, it behaves like an economic agent, a very simple concept that should apply to many things.

Mathematical objects mostly don’t seem to move around, which makes it hard for us to observe the reallocation process. It would be interesting to find a way to give sets some kind of impetus and see if a virtual governor patterned after the Cartesian product could get the sets to assemble into the optimal form.

Virtual governors are particularly important because they can be used to solve highly complex problems. They are system-level preferences, so if we edit the governor, we edit the system-level preference. If the system is very complex, but the virtual governor relatively easy to manipulate, then you can change the virtual governor’s goals and then have it do the hard work of regulating the complex system for you. Perhaps complex mathematical structures could be deduced or important theorems proved by some means of arranging the desired final outcome and having that outcome manipulate a mathematical system into producing the right system of relationships or logical steps for a proof.

Thought you might like this.

https://berggruen.org/eu/news/the-mind-as-a-city-a-systems-view-of-consciousness-by-ian-reppel