Externalities are defined with respect to a virtual governor

An externality is a neighborhood effect, a cost imposed by one person on another. So say that Alice throws loud parties at night that keep her neighbor Bob awake. Is this an externality? The answer is that it depends on how the interaction is mediated. If the interaction took place through the price system—if Alice paid Bob for the right to throw parties, for example—then there is no externality. But if Alice didn’t pay for anything, or if Bob didn’t have the opportunity to pay Alice to party less, then there is an externality.

The price system is a virtual governor for the economy, so it’s possible that externalities and virtual governors have some special relationship, where the question of whether something is an externality is determined from the perspective of the virtual governor. This idea makes intuitive sense, and there’s an interesting example from mathematics as well as economics.

Intuitively, the relationship between externality and virtual governor makes sense because externalities are only meaningful with respect to a system-level goal, which the virtual governor embodies. To see this, consider that an externality is a useful concept because it explains the presence of inefficiency, but efficiency is defined with respect to a goal, and whose goal are we talking about? Alice’s goal is to party, and Bob’s goal is to sleep. The resolution isn’t compromise but the creation of a new system-goal to which they are both aligned. It is from the perspective of this system-level goal that Alice parties too much or too little, and it is by adjusting price signals that Alice “knows when to stop”—raising the price if she parties over the optimal amount and lowering the price if she parties under the optimal amount.

An externality is a “wrong” object, something extraneous (negative externality) or missing (positive externality). There is no object that’s wrong in isolation. Instead, it’s all about what the system is trying to achieve. That’s what determines whether there’s too much or too little of something. And because a system such as the economy is made of people with competing goals, the question of whether there’s too much or too little of something isn’t determined by some vote that lumps people’s values together into a big judgment but instead the construction of a new goal, the virtual governor’s goal, that makes this determination. (Because the price system gets everyone to agree to the virtual governor’s plan, if the virtual governor wants Alice to be partying a certain amount, then if Bob is integrated into the price system, he must have agreed to Alice’s plans.)

Mathematical objects also can be analyzed in terms of extraneous or missing objects. Consider the set of prime numbers. This is a set that can be used to generate all the natural numbers greater than one via multiplication. However, many other sets can do that—for example, the union of the set of prime numbers with the set {10}. Other sets can do almost as good of a job, like the set of prime numbers minus the element 2. This set, missing one key element, can generate all of the odd numbers greater than 1 via multiplication.

The set of prime numbers is special because it is the optimal set for producing all of the natural numbers greater than 1 via multiplication. Any other set has extraneous elements like 10 or is missing elements like 2 (or is uniquely isomorphic to the set of prime numbers). But the optimality of the set of prime numbers isn’t in the set itself. There’s nothing wrong in isolation with the set of prime numbers and also the element 10, and there’s nothing wrong with the set of prime numbers but missing the element two. The optimality of the set of primes is instead in the relationship between the set and the goal of generating a structure—mathematical morphogenesis—as defined by a universal property. (Free objects might indicate what it means to “get something for free” from math?)

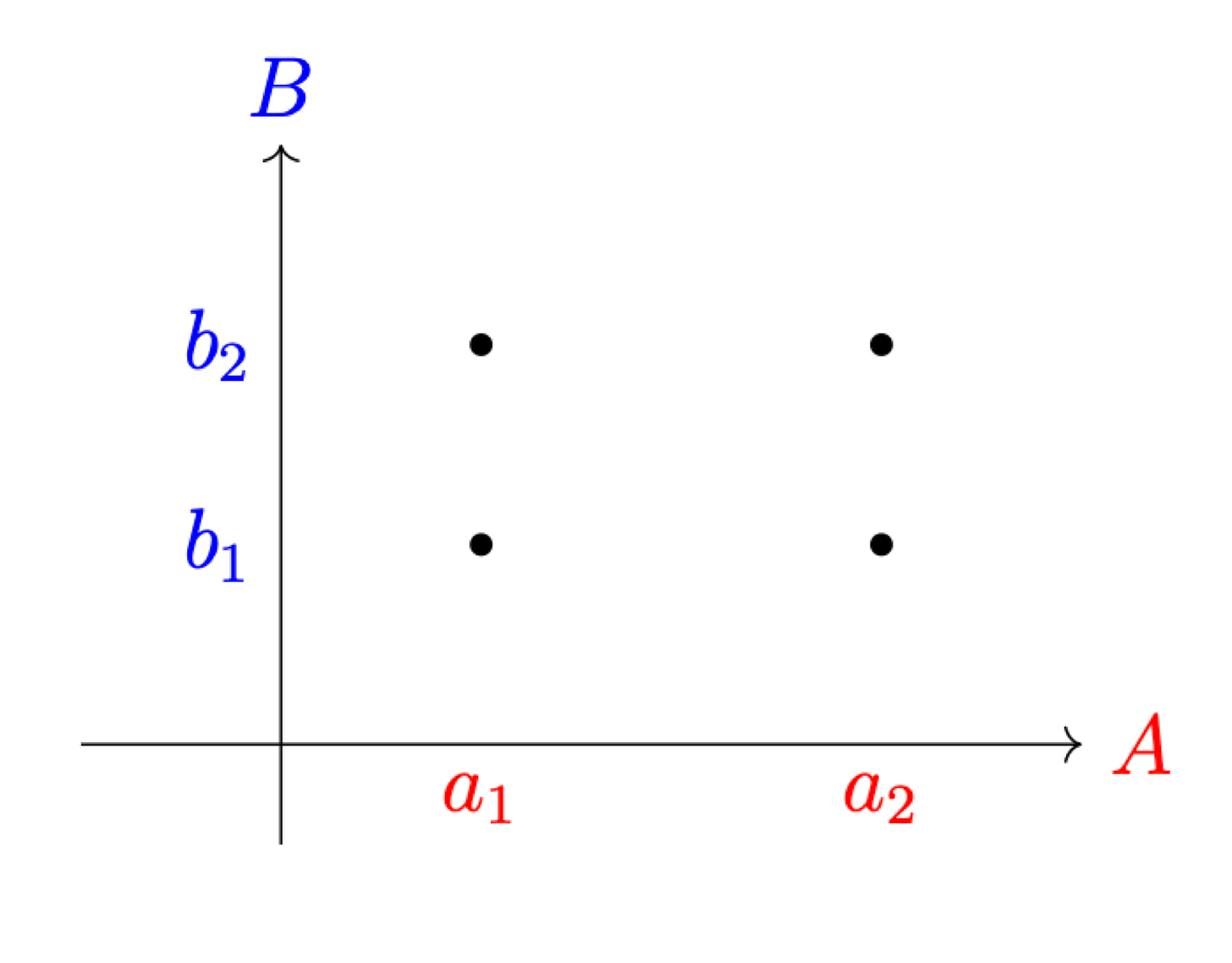

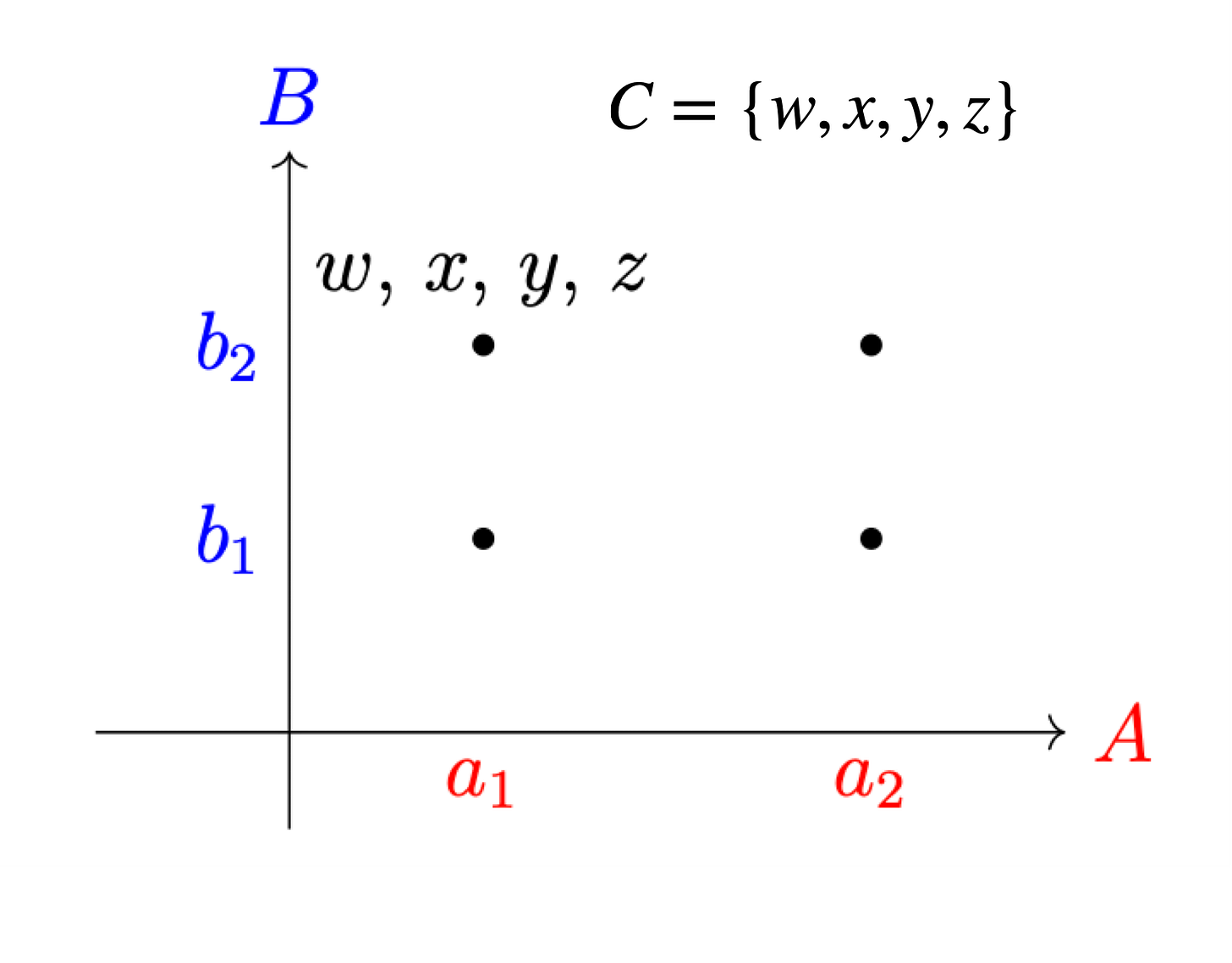

Universal properties are virtual governors, and indeed we observe that universal properties tell us when there is too much or too little of something in math. The Cartesian product is a really clear example of how this works. If A and B are each sets with two elements, then the task of the Cartesian product is to fill out the Cartesian plane in an optimal way.

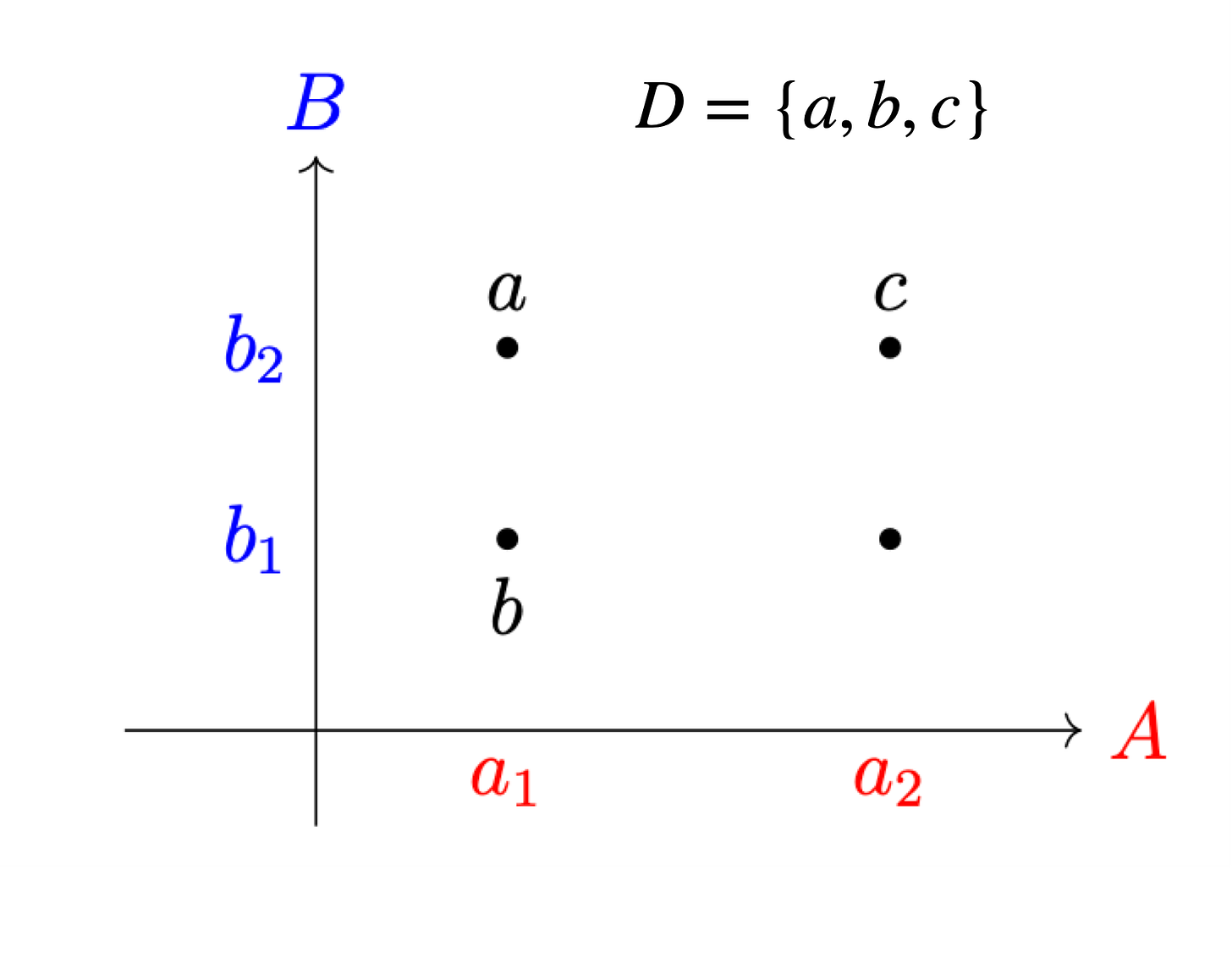

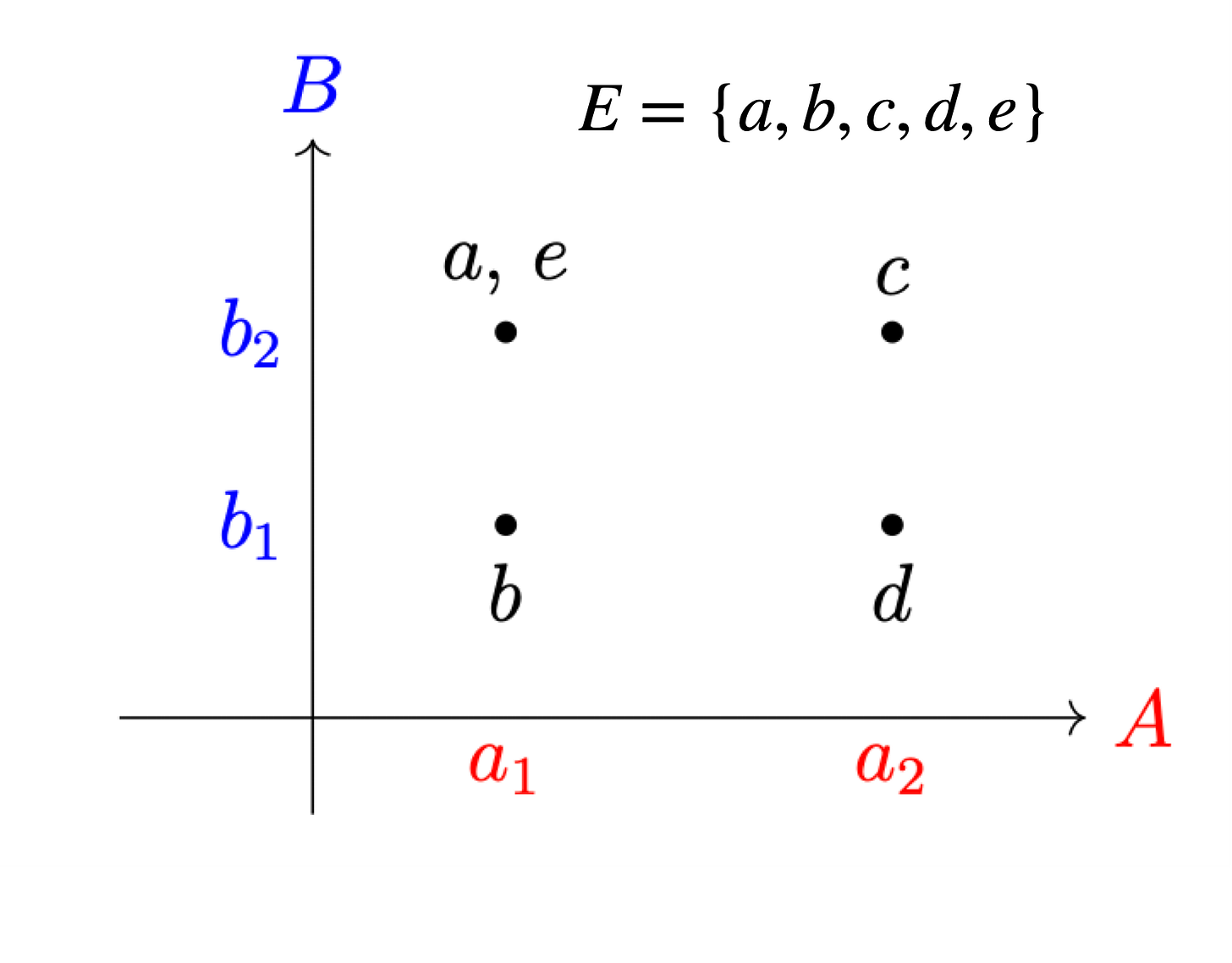

Obviously, you want a four-element set to fill out the plane. A three-element set or a five-element set will have too many or too few elements to do the job properly.

Obviously, there’s nothing wrong with a three-element set or a five-element set. In a vacuum, the three-element set is not missing anything, and the five-element set does not have anything extraneous. However, the optimization problem as defined by the universal property the product tell us whether something is missing or extraneous. Even a four-element set is not sufficient by itself. The “resources” the set brings to the problem have to be allocated correctly. Otherwise, once again, you have “too much” going to one place and “too little” going to another, from the perspective of the virtual governor that is the Cartesian product.

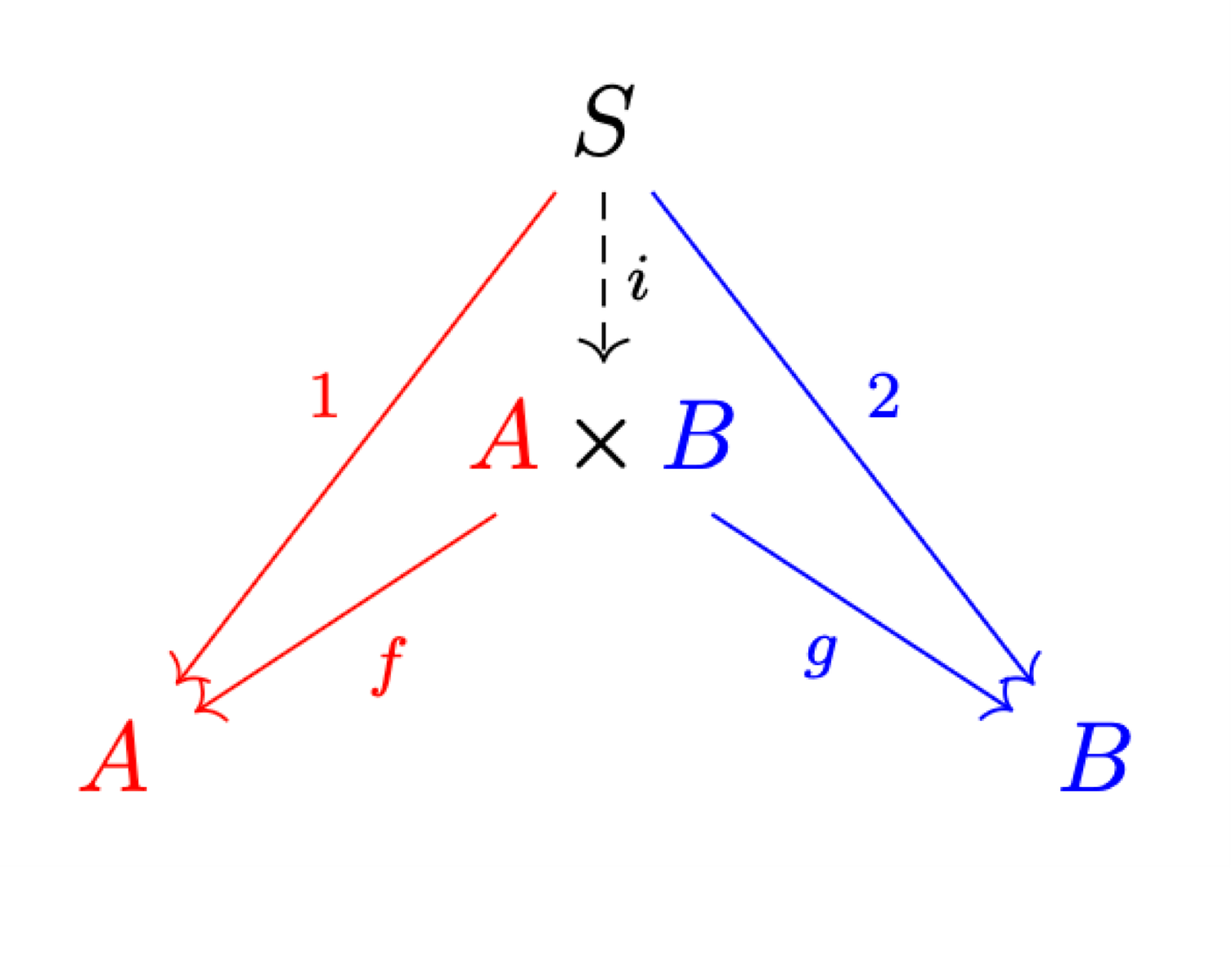

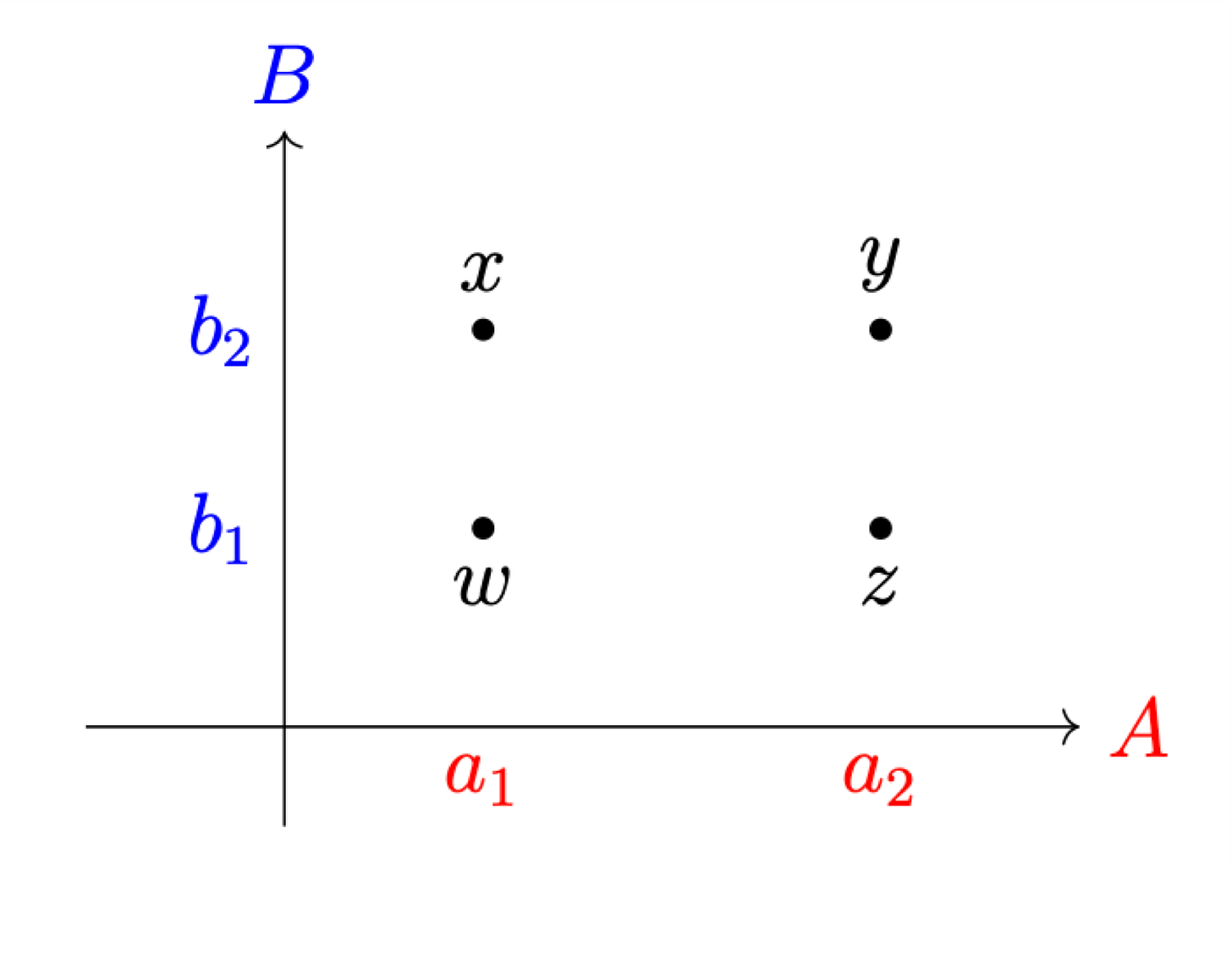

The virtual governor that is the Cartesian product doesn’t even need to check the individual solution of each use of each set. Instead, it can just compare each set to a template for solving the problem and see if there’s any meaningful difference between the sets:

The fact that mathematical systems have the same relationship between virtual governors and externalities that physical systems do corroborates the idea that externalities have nothing to do with the object-level interaction and everything to do with the system-level plan. This is why externality is hard to define in economics: if the system felt there was too much or too little of something, why wouldn’t it change that?

This also indicates the relationship between virtual governors and alignment: it is the virtual governor that says what is external and what is internal to system. Things that are internal are taken care of; things that are external are not.

For more on extraneous elements in math, see here: