Can math get cancer?

One way of thinking about cancer is that it refers to cells that are separated from the bioelectric system that coordinates the individual cells into a collective self. Cancer cells aren’t malicious, but they are self-interested, and the self that they are interested in does not include the rest of the body when not sharing interoceptive signals with it through bioelectricity.

If bioelectricity is an example of a price system, then there is an obvious economic analogy to cancer: externality. Externality refers to the effects of activities that aren’t connected to the rest of the economy via the price system. As a result, harmful activities can perpetuate throughout the economy’s body just like with cancer.

The generalization of cancer to externality is useful because it lets us study the phenomenon from new angles. First of all, having cancer means the presence of a bad thing, but externality can also mean the absence of a good thing. For example, a factory that pollutes beyond the optimal amount is producing an externality, but someone who doesn’t get a vaccination is also producing an externality. Thus, there may be things other than cancer in an organic body that can be studied via the lens of externality, applying the same bioelectric theory of cancer to the body’s failure to produce desirable things in sufficient quantities.

Second, the generalization of cancer to externality lets us think about cancer in terms of extraneous elements, inefficiency, and production possibility frontiers. An externality can be thought of as an element present in a system that shouldn’t be present, or an element missing from a system that should be present. Externality can also be thought of as the general explanation for inefficiency: whenever inefficiency is present, it must be caused by an externality. Inefficiency, in turn, can be understood with respect to production possibility frontiers: an efficient system can only move along the frontier, trading off between desirable properties, while an inefficient system can advance toward the frontier, potentially improving on desirable properties without making tradeoffs between them.

With this generalization, we can think about the potential presence of cancer-like elements in math. For example, consider the set of real numbers with an extraneous element, e, throw in as well (The element e is not the calculus e, just a generic extraneous element—our candidate for externality):

This set is not the real numbers, but it can do everything the real numbers can do. All you need to do is append “except for e” to the axioms that uniquely determine the real numbers. So this set does the job that the real numbers do, but in a worse, stupider way. In other words, we have an inefficient version of the real numbers.

As we expect of the theory of externality, the inefficiency has a clear source: the extraneous element e. Since this element is extraneous and responsible inefficiency, it matches what we expect of an externality.

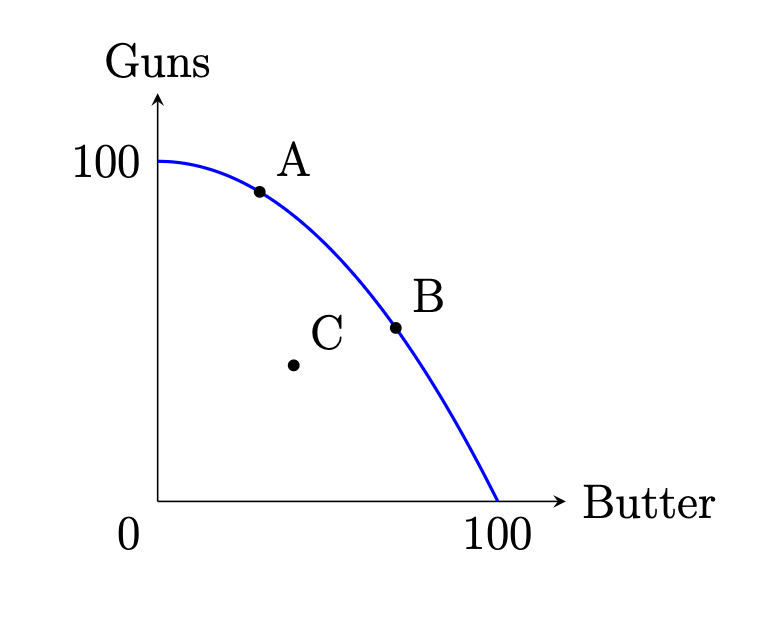

We can verify the presence of inefficiency by plotting things on a production possibility frontier. The example plotted below shows a tradeoff between the production of guns and the production of butter. The blue line depicts the production possibility frontier, which represents the technology limitations of the economy. Anything on the blue line, like points A and B, is efficient: the technology of the economy does not allow for the production of more butter without producing fewer guns or vice versa. So if the economy is at point A and decides to produce more butter, it can do so by going to point B, which means producing fewer guns. However, if the economy is at an inefficient point below the production possibility frontier, such as point C, then it can produce more guns and more butter simultaneously. So inefficient systems can avoid making tradeoffs. For example, the economy could navigate to the right horizontally from C until it reaches the blue line, producing more butter without producing fewer guns, which is impossible when you’re already at the blue line.

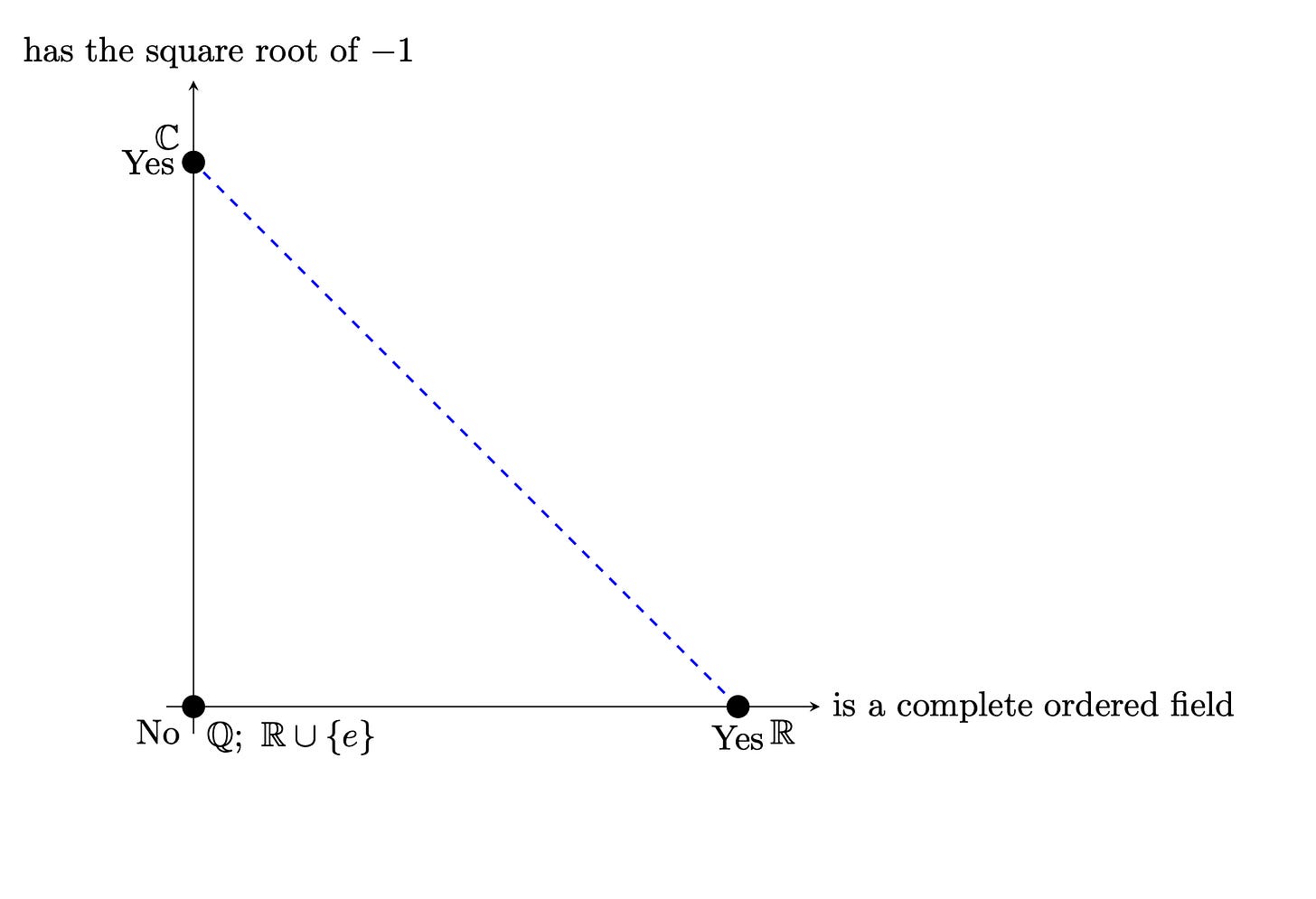

Now let’s compare to a mathematical tradeoff such as the tradeoff between being a complete ordered field and being able to define the square root of negative one. The real numbers are a complete ordered field but cannot define the square root of negative one without giving up the property of being a complete ordered field, and vice versa for the complex numbers. We can depict this on a production possibilities frontier like so:

Both the set of rational numbers and the set of real numbers with the extraneous element, e, sit beneath the blue line. I think the set of rational numbers can be intuitively albeit very very informally thought of as being a system that has less technology than the real numbers, and so doesn’t belong on this graph. Whereas the set of real numbers with the extraneous element included can do everything the real numbers can do and so intuitively has the same technology. As with the point C in the prior graph, we can have the set of real numbers move horizontally, increasing its possession of a desirable property (going from not a complete ordered field to being a complete ordered field) by simply abandoning its extraneous element without cost, i.e., without going down vertically the way that the point A in the prior graph can only move horizontally by going down vertically toward point B.

This argument, while obviously informal and handwavy, does indicate that math seems to behave in the way that economics would expect of systems that have extraneous elements. So can math get cancer? If you add extraneous elements to a system, you have to keep adding to the axioms to maintain the behavior of the system: ignore e, and f, and g, etc. With the accumulation of extraneous elements, axioms go from short and sweet to a lengthy sequence of caveats. This feels unhealthy, as cancer should be, even if the mathematical system will never die the way an organism will.

Cancer should be curable by reconnecting the extraneous element to the rest of the body via the cognitive glue. Functions are a reasonable guess for a cognitive glue in math, so it’s noteworthy that if we factor the set of real numbers with an extraneous element through just the set of real numbers, then we remove the inefficiency, as the extraneous element is assigned a functional task. The fact that functions require that every element in the domain be mapped may be a hint as to why functions are a good candidate for a mathematical cognitive glue—you can’t have an extraneous element in the domain of a function.

Cancer may not be very deadly or important in mathematics. If math is all about the study of very low agency patterns, then it’s possible that they’re too low-agency for cancer to be very harmful or noteworthy. But at the least, I think it’s interesting that we can think about finding cancer-like things in mathematics via the bridging concept of externality.

This is an interesting thought (and timely, since I was lecturing today about the axioms of measurement theory). But I think in this case, there's a sense in which the problems that exist aren't problems for the elements in the system, but for the user from outside the system. I don't quite see how this particular type of system can get the elements of the system to have goals or desires in the way that cells and organisms can. But it would probably work with some more complicated sort of mathematical system.

One other thing I was thinking when you talk at the end about functions, is that the obvious way to deal with this element is to extend the rules to it, and that's how you get fields of polynomials over R. The fact that the math does well with this extension suggests that whatever's going wrong here is importantly different from cancer and other externalities.

Also, the example strikes me a bit like the extended reals (which a student asked about in class today), where all the rules for addition, multiplication, and subtraction work fine for the finite elements, and sorta work for +\infty and -\infty, but only in somewhat broken ways. But the system still has some advantages that make it sometimes the right system to use.

Do you consider non-standard models of the Naturals to have externalities?